Thomas Hart Benton 1889–1975

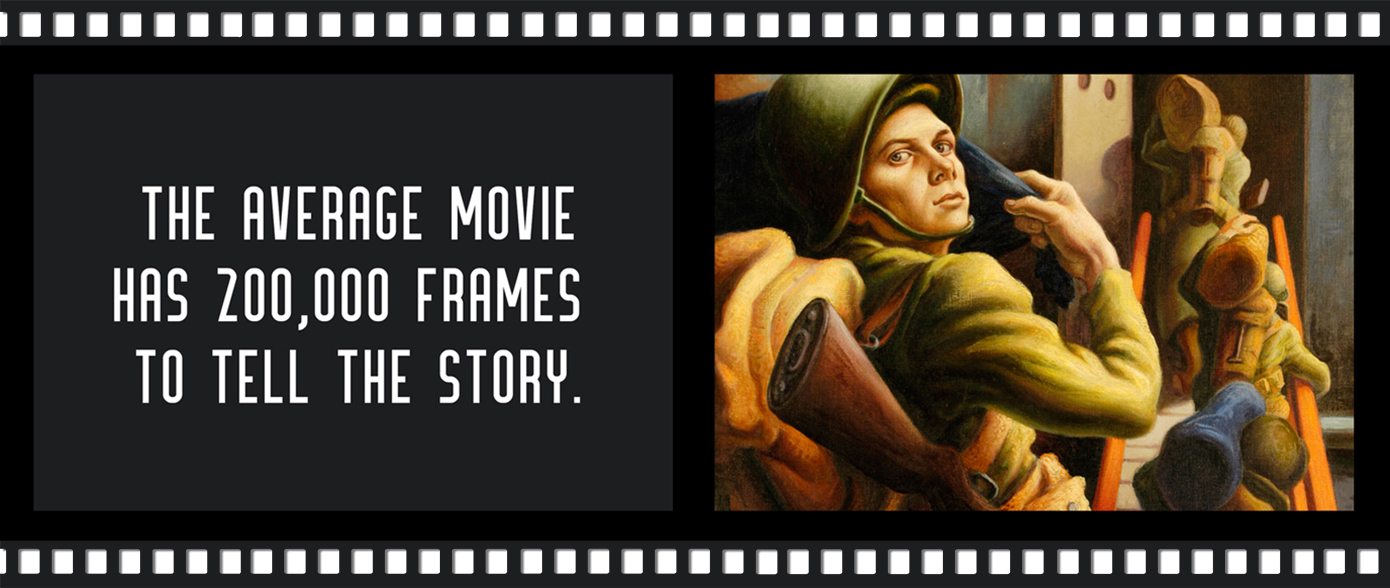

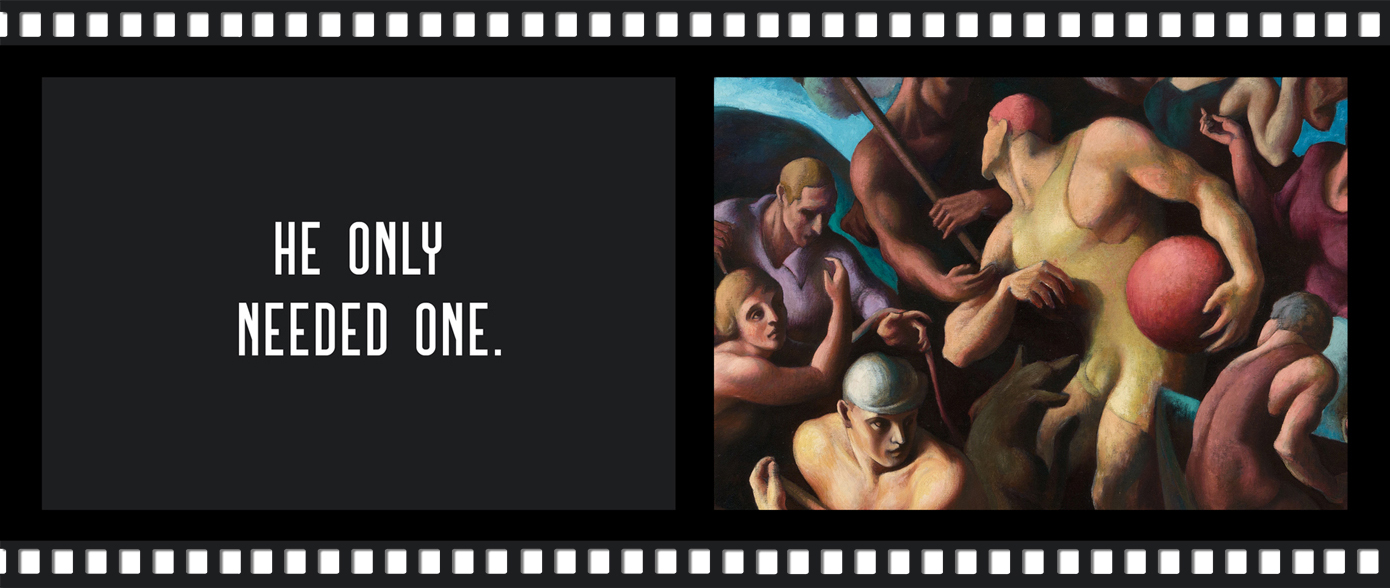

For over a century, movies have captured our imaginations, immersing us in the narratives of distant wars, home-town dramas, the wild west, and political intrigue. The same holds true for the works of Thomas Hart Benton. Inspired by Hollywood cinema and human nature, this quintessentially American artist applied the techniques of early movie-making to depict compelling stories in each of his vibrant, larger-than-life paintings.

National Tour Sponsor

Organized by the Peabody Essex Museum in collaboration with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. The exhibition was made possible in part by Bank of America and a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities: Celebrating 50 years of excellence, with additional support from the National Endowment for the Arts. The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Image Gallery

Thomas Hart Benton, Hollywood, 1937–38. Tempera with oil on canvas, mounted on panel. 56 × 84 in. (142.2 × 213.4 cm). The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Bequest of the artist, F75-21/12. Photo by Jamison Miller. Art © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank. Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Thomas Hart Benton, Self-Portrait with Rita, c. 1924. Oil on canvas. 49 × 39 3⁄8 in. (124.5 × 99.9 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jack H. Mooney, NPG.75.30. Photo courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY. Art © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY [THB-009]

Thomas Hart Benton, Shipping Out, 1942. Oil on canvas. 40 × 28½ in. (101.6 × 72.4 cm). Private Collection. Photo by Chip Cooper. Art © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank. Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Thomas Hart Benton, People of Chilmark (Figure Composition), 1920. Oil on canvas. 65 5⁄8 × 77 5⁄8 in. (166.5 × 197.3 cm). Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966, 66.468. Photo by Cathy Carver.

Thomas Hart Benton, Portrait of a Musician, 1949. Casein, egg tempera, and oil varnish on canvas, mounted on wood panel. 48 1⁄ 2 × 32 in. (123.2 × 81.3 cm). Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri–Columbia, Anonymous gift, 67.136. Art © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

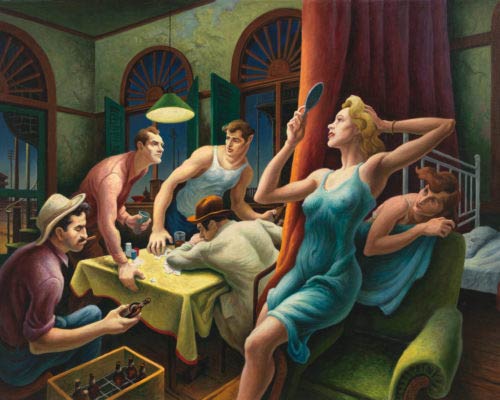

Thomas Hart Benton, Poker Night (from A Streetcar Named Desire), 1948. Tempera and oil on linen mounted on composition board. 36.00 x 48.00 in; Frame: 44.75 x 56.81 x 3.13 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Mrs. Percy Uris Bequest 85.49.2. Art © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Additional image credit from video ad:

Thomas Hart Benton, Indifference, 1942. Oil on canvas. 21 x 31 in (53.3 x 78.7 cm). State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, 1944.7. Art © T.H. Benton and R.P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Bio & Timeline

Born in Neosho, Missouri to an influential political family, Thomas Hart Benton was groomed from an early age to continue his family’s legacy. At 16, his father sent him to the Western Military Academy with the intent of grooming him towards this end, but Benton was more inclined to pursue an interest of art. With the support of his mother, he enrolled in The School of The Art Institute of Chicago in 1907. This was soon followed by a stint at the Académe Julian in Paris, where he met with other North American artists such as Diego Rivera and Stanton Macdonald-Wright.

Moving back to the United States in 1912, and newly immersed in the latest modernist styles, Benton further developed his talent as a painter and illustrator working for the US Navy. This included a time working as a “camoufleur,” during which he documented the camouflage patterns of naval ships entering Norfolk harbor. It was also during this period that Benton began his fascination with moviemaking, designing and painting scenery for film sets and sound stages during the 1910s.

In the early 1920s, Benton moved to New York and declared himself an “enemy of modernism,” favoring naturalistic and representative work that focused on American Epics. Relatively unknown to this point, he captured national attention in 1932 when he won a commission to paint murals of Indiana life for the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago. He focused his mural on everyday people and their activities—not all of it positive. Some of the more difficult and horrific episodes of the mural series ruffled more than a few feathers, and set the course for a controversial career in which he held fast to a desire to paint life as it was, and not simply as we might wish it to be.

Capturing the Story in Epic Cinema Style

American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood is the first major traveling exhibit of Benton’s work in more than 25 years.

Having worked for a time as a set painter on silent films, the movie industry heavily influenced Benton’s technique from early in his career. His style combines old European mastery with Hollywood cinematography to capture larger-than-life narratives with the illusion of three-dimensional space and a sense of motion and projected light. When crafting his paintings, Benton even adopted several movie-making techniques, including the use of clay models to study shadows, and the use of storyboards to plan his murals.

In addition to his use of cinematic styling, Benton also shared an interest in many of the film industry’s favorite themes. War, the frontier, domestic turmoil, and pursuit of the American dream all found their way beneath his brush.

In 1937, Life Magazine commissioned Benton to represent the still burgeoning Hollywood, in which he set out to capture the behind-the-scene stories of the movie industry’s golden age. In typical Benton fashion, he used this project to lay bare the realities of Tinseltown’s establishment and culture—good and bad alike. His hundreds of sketches and some 40 resulting ink-and-wash drawings that Benton referred to as “notes,” focused on everything from bustling set design, eager casting lines, and meticulous film editors—down to the intrusiveness of paparazzi, the backroom dealings of jaded executives, and the prevalent exploitation of Hollywood starlets.

In 1939, Benton again crossed paths with Hollywood when 20th Century Fox commissioned him to create promotional materials for the film adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath. Benton would continue this relationship with Hollywood promotion with projects like The Kentuckian.