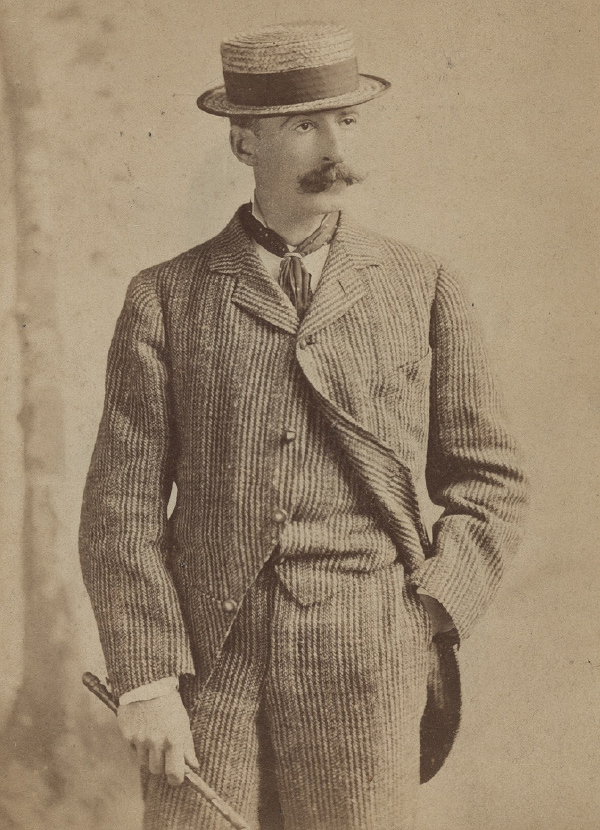

Winslow Homer (1836–1910) is considered by many to be America’s greatest nineteenth-century painter. Raised in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he began his artistic career as a commercial printmaker in Boston before moving to New York in 1859 and briefly studying oil painting. In October 1861, six months after the outbreak of the Civil War, Harper’s Weekly sent Homer to the front in Virginia as an artist-correspondent. His Civil War paintings established him as a serious and successful artist and showcased his interest in merging narrative with emotional weight—his canvases display an amazing awareness of the war’s consequences and impact.

The 1860s and 1870s marked a period of experimentation for the artist. In 1866–67, he made a trip to France and, afterward, adopted the practice of painting directly from nature, emphasizing natural light and bold colors. Critics celebrated his work from these decades for its “truth to nature,” what many described in varying terms as “purely American,” or—in the words of one—as “Yankee in character as the ‘stars and stripes.’” Homer’s reputation rested largely on the perceived directness and immediacy of his depictions, as well as the quintessentially American character of his subjects: independent farmers and outdoorsmen on the one hand, women at leisure and mischievous country children at play on the other.

From May 1881 to November 1882, Homer lived in the small fishing village of Cullercoats on the northeastern coast of England. Before his departure, Homer had begun to show an affinity for British art, and the move to Cullercoats offered him an opportunity to develop this new interest. Remote and bound to time-honored traditions, Cullercoats and its inhabitants symbolized a rugged authenticity that also allowed Homer to explore new subjects and nurture his growing fascination with the sea. Critics noticed the change in style at once: “He is a very different Homer from the one we knew in days gone by,” wrote one. Now Homer’s pictures were “works of High Art,” and his seascapes conveyed the “power” and “majesty” of the subject, described as “nothing short of grandeur.”

Homer’s nearly two years in England influenced not only his creativity, but also where he chose to live. In 1884, he permanently relocated from New York to the rocky, windswept coastal peninsula of Prout’s Neck, Maine, an American equivalent of the remote English north. Homer lived at Prout’s Neck until his death, only occasionally venturing to nearby regions and to Florida and the Caribbean, where he produced shimmering watercolors. Homer became especially concerned with the role of the human figure and with narrative in his compositions, struggling with how prominent either should be. Increasingly he instead concentrated on capturing the magnificence and spectacle of the sea and its shifting moods. Today, these Maine seascapes remain among Homer’s most famous works, appreciated for their dazzling brushwork, emotional impact, and hints of modernist abstraction.

Membership

Membership Visit

Visit