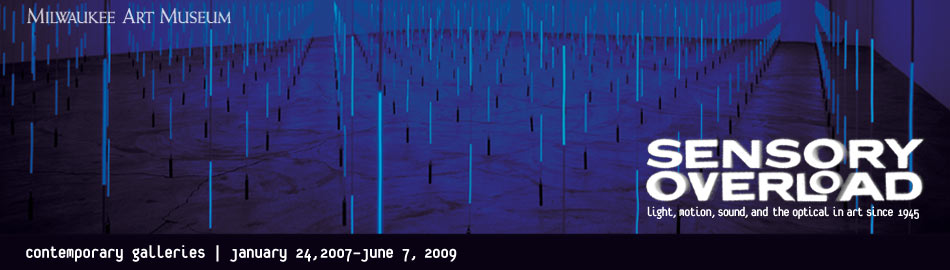

SENSORY OVERLOAD: Light, Motion, Sound, and the Optical in Art Since 1945

The Spirit of The Century

At the turn of the twentieth century, artists began using industrial materials

and movement (literal and optical) to reflect the mechanical and electrical

revolutions that were radically reshaping the modern world. The Italian

Futurists and Russian Constructivists advocated that all art be based on

speed, movement, and industrial materials, leading to the first kinetic

sculpture by Naum Gabo in 1920. Russian émigré László Moholy-Nagy

introduced these ideas to the curriculum of the German Bauhaus, declaring

the machine “the spirit of this century.” Succeeding Moholy-Nagy in

1928, Josef Albers continued to advance the application of science to art,

developing theories using color and geometry to create optical effects.

When the National Socialists forced Bauhaus teachers to expatriate from Germany, the location of this creative ferment was effectively transferred to the United States, where, in 1936, a group of American artists influenced by early Modern European art formed the American Abstract Artists group. Among the founders were Burgoyne Diller and Fritz Glarner, who boasted among their members the recently immigrated Josef Albers.

Le Mouvement

After World War II, the ideas generated at the Bauhaus about abstraction,

motion, and color catalyzed an international exploration of Kinetic art.

In 1955, Galerie Denise René, Paris, organized the first exhibition of Kinetic

art, Le Mouvement, introducing works by Yaacov Agam, Pol Bury, Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp,

Robert Jacobsen, Jesús-Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely, and Victor Vasarély. During the late 1950s

in Düsseldorf, Germany, Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and, later, Günther Uecker

founded a Europe-wide movement named Group Zero that was against

the use of technology for war, and in support of its use in art.

By the 1960s, Kinetic art had spread to the U.S. The Howard Wise Gallery, New York, organized numerous exhibitions between 1960 and 1970. In 1968, the Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, organized The Magic Theatre, an unprecedented sensory exhibition developed by engineers and artists. Capturing the rising trend, popular theorist Marshal McLuhan looked specifically to artists to transform our postwar nation into a technological culture: “The serious artist is the only person able to encounter technology with impunity, just because he is an expert aware of the changes in sense perception.”

Op Art

After the National Socialists closed the Bauhaus in 1933, László Moholy-Nagy

and other Bauhaus instructors fled Nazi Germany and came to the United

States, where they spread their art and design theories at schools such as Black

Mountain College, Illinois Institute of Design, MIT, and Yale University. As pupils

of Josef Albers at Yale, artists Richard Anuskiewicz and Julian Stanczak were

informed by the Bauhaus artist’s color theories and developed them into what

has become known as Op art. In a 1964 article, Time magazine coined the term

“Op art” to describe this new, intense visual art style that had erupted across

the Western world and spread from art into fashion and graphic design.

American Op artists were particularly influenced by Yaacov Agam, Bridget Riley,

and Victor Vasarély to create illusions of motion and volume by employing

moiré patterns and shifting images that disrupted the retinal focus and created

after-images. Op art preyed upon the fallibility of vision to create the sense of

movement. The fashion for this art movement crested in 1965 with a series of

important international exhibitions.

The Projected Image

A number of people, including Thomas Edison (the inventor of the light bulb),

experimented with various motion picture apparatuses in the mid-1890s.

Incorporating such scientific pursuits into an art form, László Moholy-Nagy

strove to explore “the new culture of light” in creating his Light-Space

Modulator (1930), a kinetic sculpture with an electric motor that projected

light. Through the introduction of television, video recorders, and

computers, artists gained access to the new media of light, sound, and

motion. Artists began to utilize the black box environment of the cinema as

a theater for creating immersive artistic experiences that stretched pictorial

imagery across physical space. At this time, we see the confluence of art film,

theater, and Kinetic art developed into video and installation art, arguably

one of the defining artistic genres of contemporary art.

Geometric Abstraction

The extraordinary popularity of Op art spread to fashion and design; yet, the

intensity of the visual stimulation exhausted the retinas of a generation and

its vogue quickly faded in the late 1960s. Critics began to deride the trend as

based simply on visual effects. As a response to the perceived excess of Op

art and its predecessor Abstract Expressionism, artists and critics sought to

reduce art to simple geometric forms and pure, brilliant color. In 1964, critic

Clement Greenberg curated an exhibition titled Post Painterly Abstraction, in

which he endeavored to define a formal theory for the evolution of painting

from the gesture of Abstract Expressionism to a hard-edged abstraction that

created an “optical” effect. Beginning in the 1950s, artists developed Color

Field painting, geometric abstraction, and, eventually, Minimal art based

on these principles. Painters Gene Davis, Al Held, and Frank Stella created

differing visions of art concerned with the direct experience of color and

form. Frank Stella famously proclaimed: “What you see is what you see.”

Touch of the Hand, Click of the Mouse

Kinetic art, geometric abstraction, Op art, and the projected image

still influence artists working today. Technological advances over the past

twenty-five years, from the personal computer to wireless communications

to digital editing and imaging in video, have provided artists with new

tools. Artists responding to these new technologies continue to adopt the

visionary ideas of the Bauhaus, adapting them for the twenty-first century.

Josiah McElheny employs the Walk-In Infinity Chamber technology to

present his finely crafted versions of 1950s modern design in a reflective

box that suggests the melding of past and future in a continuous space.

As our world becomes ever more based in the flat digital screens of televisions, computers, and cell phones, people increasingly crave the human hand in art and artwork that creates a pure sensation. Critic Dave Hickey prophesized that, “the issue of the nineties will be beauty” (1993). Indeed, a new generation of artists such as Michelle Grabner, Bruce Pearson, and James Siena has made works characterized by their sensuousness— rich in color and intense with pattern. These artists emulate the stimulating visual quality of Op art in the sixties, while maintaining conceptual foundations that reference advertising, architecture, and scientific systems, to create what one curator coined as “post-hypnotic.”

Contemporary Video Projections

From television to movies, the moving image is the medium that has

helped define and shape our culture. Today’s computerized formats in film,

video, and light projections have evolved dramatically from their original

models, and as in the past, artists have adapted to these technological

advances. From stop animation to digitally manipulated effects, the infinite

potential of this medium has been unleashed. Techniques such as collage

have translated to video, as demonstrated in the Museum’s 2005 exhibition CUT: Film as Found Object in Contemporary Video. Within the show, editing

techniques were likened to physical properties such as to stretch, to remove,

to match, and to arrange. For the duration of Sensory Overload, the Museum

will rotate contemporary videos from its Collection and works on loan.

The range of subjects and approaches to the medium will speak to the

techniques of CUT, among others.

See it first. See it free.

Join or Renew

Become a Museum Members today!

Join Chief Curator Joe Ketner for a brief, informative tour of works featured in Sensory Overload.