Dawoud Bey Biography

Drawn to pursue photography after viewing the exhibition Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969, Dawoud Bey embarked on a project to document the people and everyday life in Harlem, where his parents had grown up.

When I got to the Met to see the show my jaw must have dropped. I was mesmerized. Pictures. Black folks. Room after room. And other people walking around looking at these pictures. I couldn’t believe it. I felt like I had stumbled into some world I knew nothing about. It gave me a sense of photography’s documentary power, its potential to be a repository of collective memory, a doorway into another experience. That experience plus my family’s history there was probably what led me to begin photographing in Harlem in 1975.

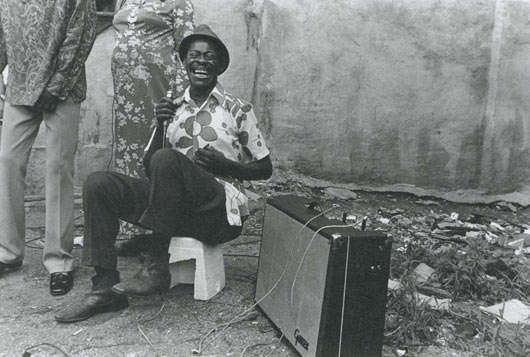

Bey’s Harlem photographs from the mid-1970s, made with a 35-milimeter camera, depicted ordinary people laughing, sitting, standing, posing, and ‘just being’ in a neighborhood that was usually portrayed quite negatively by the mainstream media. Bey wanted to acknowledge the real texture of Harlem life, which included a powerful sense of community and inspiring personalities that defied the stereotypical picture of the area in the 1970s. In 1979, when he was twenty-five years old, these works were shown in Bey’s first solo museum exhibition, Harlem USA, at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

The response of the community was the most gratifying aspect of doing the show. People who had never been to the museum before came. They told me how much they like the work and how much it meant to see these pictures on the wall. It established a meaningful dialogue with a much broader and more diverse audience, which let me know there was another audience out there, beyond the one that traditionally has gone to museums.

Dawoud Bey, The Blues Singer, Harlem, New York, ca. 1975. From Harlem USA. Gelatin silver print. 11 x 14 in.

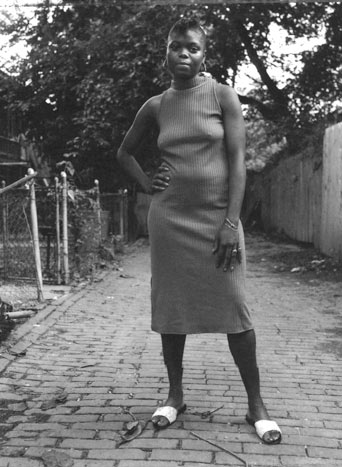

Around 1988 Bey discovered 4 x 5 Polaroid Positive/Negative Type 55 film, and began exploring Brooklyn and other areas of the country, engaging a wider variety of people in the process of making and viewing representations of themselves.

[The technique] creates an instant print, which I would give the subject, and a reusable negative from which I would make finished photographs. This now meant that I had to walk up to someone, engage them in a conversation, and obtain their consent to make the picture. I don’t think that being an artist or photographer exempts you from socially responsible behavior. Working this way allowed me to confront the implicit hierarchy that I believe is established when one photographs people. It is a hierarchy that has to privilege the photographer or the one who makes and is in possession of the image.

Dawoud Bey, A Young Woman Between Carrolburg Place and Half Street, Washington, DC, 1989. Gelatin silver print. 24 x 20 in.

When the Addison Gallery at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, awarded him an artist residency in 1992, he changed his approach yet again. This time he worked in color with an extra-large format 20 x 24 Polaroid camera, which produced unique photographic prints that self-developed minutes after exposure; only five such cameras existed, and one was located in Boston. So after spending several weeks getting to know students at Phillips Academy and the local public school, Lawrence High, he began taking students with him to Boston to make their portraits. In characteristic fashion, Bey pushed the limits of his medium even further when he got them there, increasing the intricacy of his portraits.

In the Polaroid studio, when I was pinning the works to the wall as they were being made, I decided that I liked them better paired than individually. At that point I began the double portraits, with one image giving the appearance of the private self and the other suggesting the public. Initially it was about appearances, how someone looks when one is unaware of the camera’s presence, which is so much of what photographs made in the streets are about, and how someone looks when they are directly engaged with the camera and the photographer. I wanted, in the context of the studio, to create these appearances and then pair them, so that a more complex reading of each would result.

Dawoud Bey, Nikki and Manting, 1992. Instant dye diffusion transfer print. 30 x 44 in.

Bey accepted a teaching position at Columbia College in Chicago in 1998 and by 2002 he had produced a new body of work, The Chicago Project. To create it, he spent several weeks in schools on the south side of Chicago making individual portraits with a 4x5 view camera of the twelve students who had been selected to participate in his project. Meanwhile, his collaborators, Dan Collison and Elizabeth Meister, interviewed them about their lives, recording their stories onto audio tape. He asked the students to produce their own photographic self-portraits as well, and these were included together with Bey’s portraits and edited versions of the audio interviews (which emitted from parabolic domes suspended in front of the photographs) when the works were exhibited in 2003 at the David and Alfred Smart Museum at the University of Chicago. Class Pictures expanded upon this format: Bey accepted several subsequent artist residencies that allowed him to work with students across the country—San Francisco, Detroit, Florida, New York, Massachusetts—where he again spent time with his subjects before recording them photographically. While he prepared his camera, he asked each student to write something about themselves. The final portrait comprises both the photograph and their written text.

My choice of the teenage subject stems, first of all, from a real belief that this society, in spite of all the rhetoric, really does not care as much about young people as it purports to…I’m trying to construct a kind of representation of the teenage subject that functions in opposition to those representations of teenagers as socially problematic or as engines for a certain consumerism. I think people tend to come to young people with a very specific sense of how they might be useful to some strategy, rather than just coming to them as a way of finding out what they’re thinking about.

Installation view of The Chicago Project, 2003. David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago

Class Pictures recognizes teenagers as unique individuals with a special relationship to society and culture—not as a group of tired ethnic stereotypes seduced by commercial media. In the process, it engages fundamental questions about representation, identity, and community, making Bey’s achievement both a timely investigation and a timeless mediation on human experience.

* Dawoud Bey quotes are drawn from Jock Reynolds, “An Interview with Dawoud Bey” in Dawoud Bey: Portraits 1975-1995 (Walker Art Center, 1995), pp. 101-115; and “Interview: Dawoud Bey and Carrie Mae Weems” in Class Pictures: Photographs by Dawoud Bey (Aperture, 2007), pp. 145-153.