Imagine Niagara Falls, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, the Yosemite Valley...untouched by the industrial age in their natural beauty and splendor. There were no road signs cluttering the landscape; in fact, there were few roads. Nature and the American Vision: The Hudson River School transcends centuries to show visitors the powerful, breathtaking vistas that defined our heritage and shaped our nation. The landmark exhibition includes nearly 50 of the most important artworks of the first half of American history—many of them monumental in size—and comes from the acclaimed collection of the New-York Historical Society. Several paintings are coming to the Museum directly from exhibition at the Louvre.

This exhibition has been organized by the New-York Historical Society.

This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Additional support provided by the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Friends of Art.

Program sponsorship provided by the Milwaukee Art Museum’s American Arts Society.

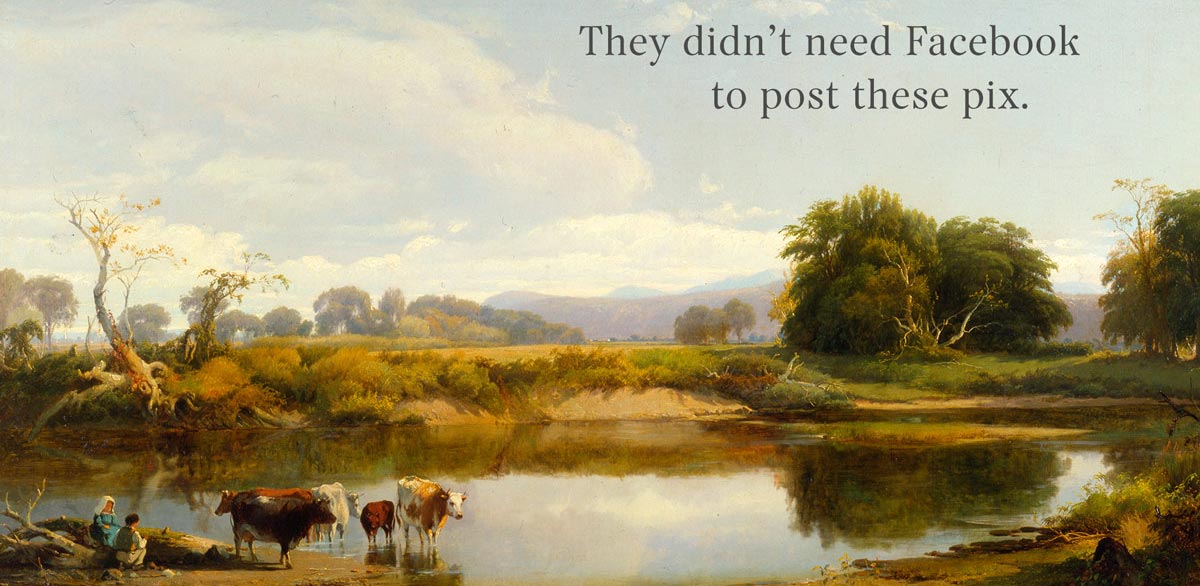

Image Gallery

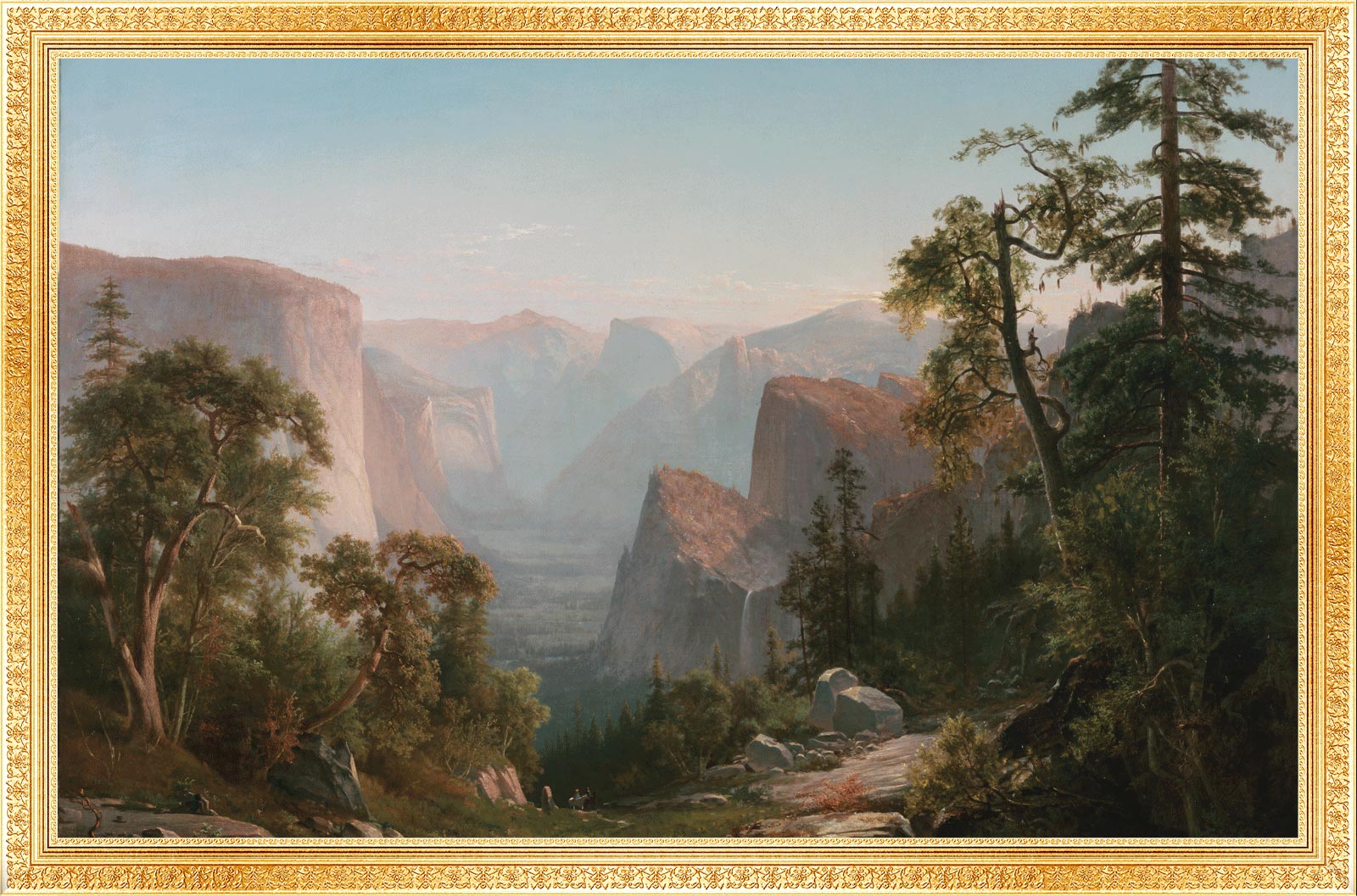

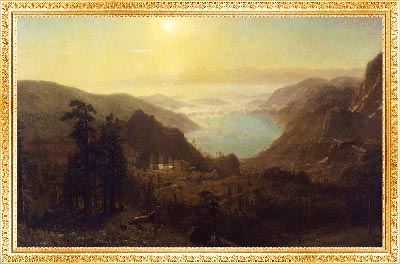

Albert Bierstadt, Donner Lake From the Summit, 1873. Oil on canvas. The New-York Historical Society, Gift of Archer Milton Huntington

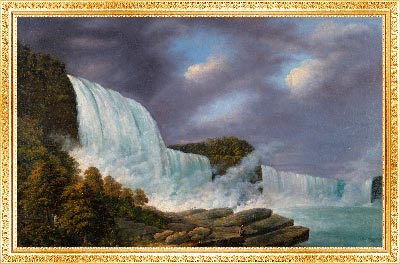

Louisa Davis Minot, Niagara Falls, 1818. Oil on canvas. The New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mrs. Waldron Phoenix Belknap, Sr., to the Waldron Phoenix Belknap, Jr., Collection

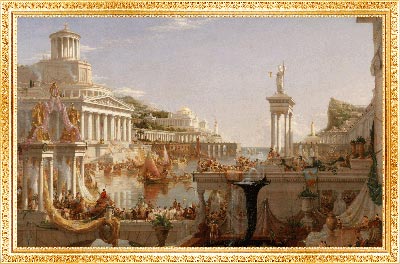

Thomas Cole, The Course of Empire: The Consummation of Empire, ca. 1835–1836. Oil on canvas. The New-York Historical Society, Gift of The New-York Gallery of Fine Arts

The Hudson River School

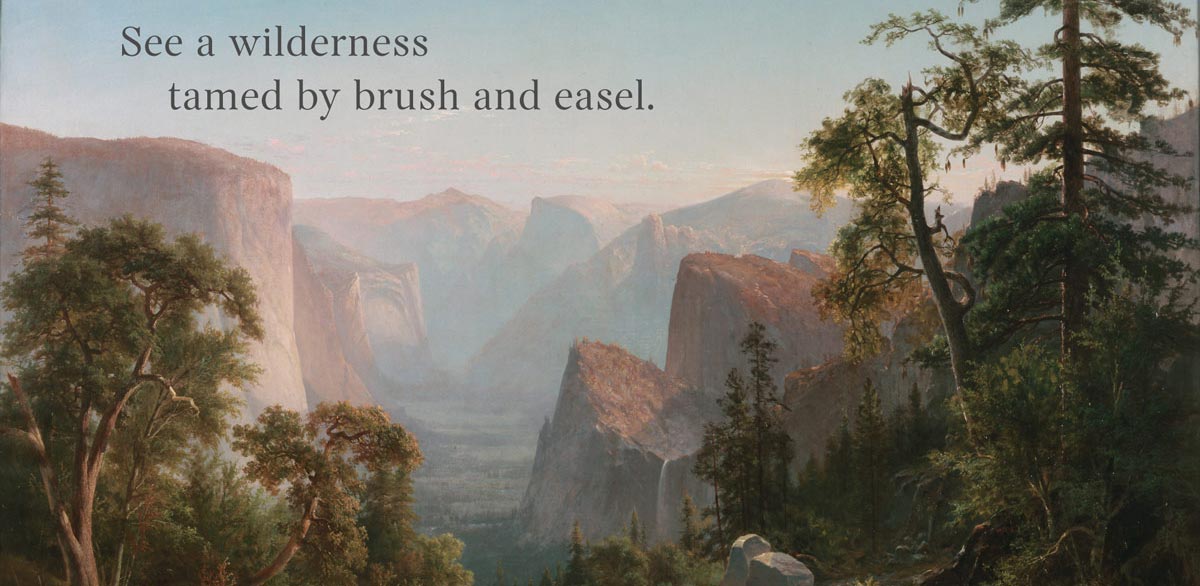

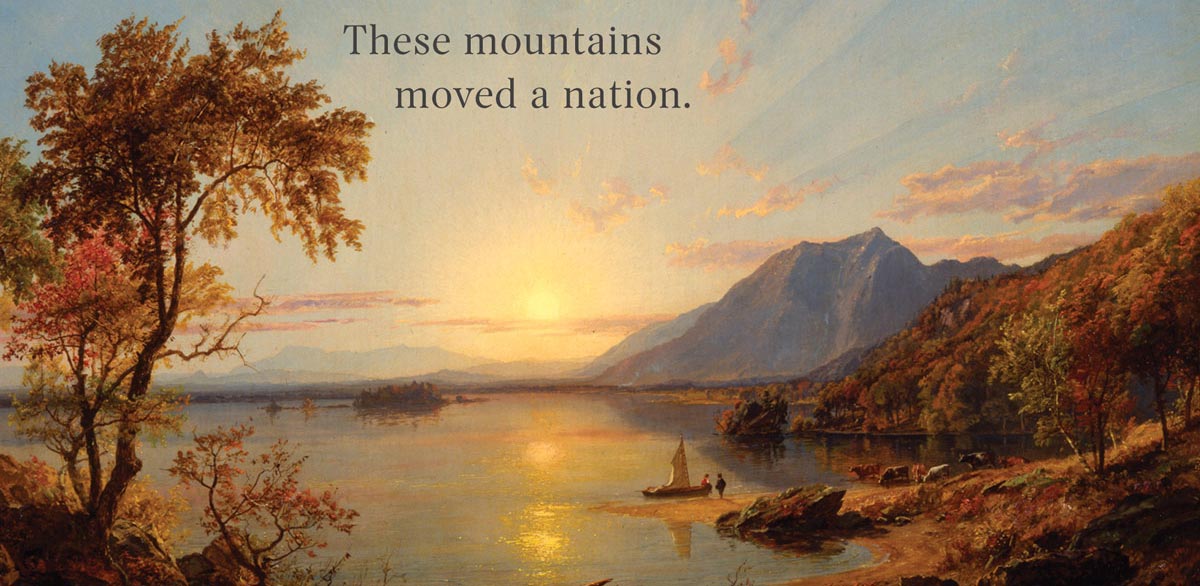

Nature and the American Vision explores and showcases the beauty and vitality of the American landscape, as seen by early settlers and sightseers, in paintings by artists of the Hudson River School. Rising to prominence in New York during the first half of the nineteenth century, this loosely knit group of painters and like-minded poets and writers—widely considered the country’s first national artistic movement—undertook grueling expeditions through the Hudson River Valley and beyond to see sites firsthand. They looked to exploration of the natural world as a resource for spiritual renewal and as an expression of cultural and national identity.

With the country expanding and emerging as a world power, painters adopted these subjects in their effort to define a particularly American visual aesthetic. By the mid-1800s, many identified landscape painting with the very qualities they believed made the country exceptional—its topographical diversity, native beauty, and seemingly endless abundance of natural resources. Their reverence for nature, and the often panoramic scale of their paintings, has been credited with spurring both nationalism and preservation movements.

Artist Bios

There are nearly two dozen artists represented in Nature and the American Vision. Learn about a few of them here.

Albert Bierstadt, 1830–1902

Albert Bierstadt, one of the most famous members of the Hudson River School, also became one of the most-traveled American artists of his time. He emigrated from Germany to Massachusetts in 1832 at just two years of age. His romantic sensibility was instilled during a return to Europe for four years of study in the 1850s and, soon after his return to America, he headed west for the first time to the Rocky Mountains and beyond with a surveying party. His 1873 work Donner Lake from the Summit, commissioned by Collis P. Huntington, might not have yielded what Huntington intended. While the transcontinental railroad is in the painting, the celebration puts nature at center stage rather than human achievement. Originally Bierstadt’s Donner Lake from the Summit had been titled Sunrise on the Sierras, but being a savvy businessman, Bierstadt knew people would more likely be drawn to see his painting if the title evoked the infamous Donner Party.

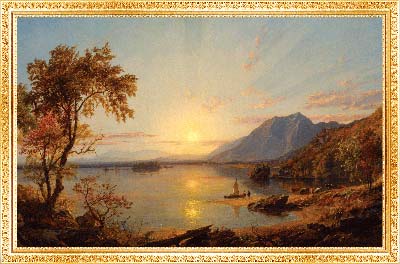

Frederic Edwin Church, 1826–1900

Born the son of a wealthy businessman in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1826, Frederic Edwin Church’s artistic talent (with a little help from family connections) led to his being accepted as the first student of Thomas Cole. Church’s early career produced landscape paintings based upon his travels around New York state and New England, some with the moralistic tone of his teacher but others with a more straightforward documentary style. Inspired by German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, Church made two trips to South America in the 1850s and produced a series of paintings that evoked the diverse climate and vast terrain of the equatorial region, including several of the inactive volcano, Cayambe. In these stunning paintings, he combined his personal experience with the visual opulence expressed in Humboldt’s opinions on landscape painting, which to him ”requires for its development a large number of various and direct impressions.”

Thomas Cole, 1801–1848

Often called the founder of the Hudson River School, Thomas Cole emigrated from England to the United States in 1819 at the age of 17. Cole, a largely self-taught artist, was inspired by the American wilderness to produce romantic landscapes filled with the drama of weather and seasons. Cole’s paintings were based upon sketches he made while traveling; he was one of the first artists to follow the somewhat uncharted course of the Hudson River into the wilderness of the Catskill Mountains. While his sudden death in 1848 left a hole in the American artistic community, Nature and the American Vision culminates in a rare presentation of Cole’s epic The Course of Empire. The five-painting series depicts the rise and fall of civilization and makes its Milwaukee debut after a six-month presentation at the Louvre in Paris.

Martin Johnson Heade, 1819–1904

Although his landscapes share this interest with the artists of the Hudson River School, and he was a friend of a number of “these movement artists,” Martin Johnson Heade does not fit easily into the idealized and drama-filled output of his fellow artists. Instead, his landscapes are eerie in their precision and ominous in their use of atmosphere, reflecting a very personal approach to the subject matter. He traveled to South America a number of times and painted a series of close-up examinations of plants and animals, hybrids of still life and landscape that create the uncanny impression that these are living characters enacting roles on nature’s stage. Although orchids were of scholarly and popular interest in the nineteenth century, critics rarely mentioned Heade’s numerous orchid-and-hummingbird subjects, probably because of the plant’s sexual connotations and the bird’s role in the flower’s reproductive process.

Images:

Matthew Brady, Frederic E. Church, ca. 1860. Daguerreotype. Library of Congress.

Matthew Brady, Thomas Cole, 1844/48. Daguerreotype. Library of Congress.